|

I decided that I wanted some roller skates.

Every year I try to get myself a birthday present, something frivolous that would normally never come up on my shopping list. One year it was the complete collection of a comic I like - although it wound up being another couple years before I actually read them. I’m often just as bad at enjoying things as I am at choosing and purchasing them - underbuying is a pervasive attitude. I kept seeing women on skates in the neighborhood, and it looked marvelous. Maybe this would be a way for me to start getting back in shape without feeling like I was working out? Just something fun and cute? Finally I went online to find adult-size skates. I was not prepared in any way for the panoply of glorious roller skates. Sparkly skates, skates in every shade of ice cream and neon, space age skates, skates with light-up wheels. Holy moly, so much rolly! I had to narrow it down from five contenders. Then I reminded myself that I am a satisficer by nature and that I can only wear one pair at a time. If I wear them out, I can always get a different set a year or two later. If you want to buy roller skates, it’s impossible to avoid learning a bit about roller derby. That’s probably the market for older babes who want to skate. I know a few people who do it and love it. In spite of the time I spent in martial arts, this is not the game for me. I am uncomfortable hitting people or feeling like I might hurt them, and I also hate anything that goes at a high speed. I knew I could skip roller derby gear without any fear of missing out. I settled on the rose gold skates. Every time I look at them, I feel the sort of swoon that I have not felt toward a material object since childhood. PRETTY! As soon as the skates went into the shopping cart, the next level of marketing attempts began. If you bought that, maybe we can convince you to buy this! Pads. Knee pads, elbow pads, wrist… braces? What even is all this stuff. I remembered the last time I skinned my knee as an adult and what a giant biohazard that was. I bought the pads. Conveniently someone else had already matched up my pretty rose gold skates with somewhat color-coordinated pads in a kit. There’s a matching helmet, but my old bike helmet is good enough for now. Meanwhile, my husband sat at my side, choosing his own skates. It basically went like this: “It’s time to pick out skates. I’m ordering mine now.” Now, I’m pretty sure I’ve only worn skates once in the past 25 years or so. My friend had a party at the skating rink. My husband, on the other hand, is a hockey player. He started with roller hockey. Not only can he skate, he is quite fast and skilled on both roller and ice skates. For him to choose a pair of skates was only a marginally harder sell than, say, a pizza. He was more worried about my choice of skates than his own. Obviously he was going to get inline skates - rollerblades - because they are faster and feel similar to ice skates. He has been talking about playing hockey again, and this would be a good way to get his ankles conditioned. Equally obviously, I was going to get 1970’s-style disco skates. I’ve never worn rollerblades and didn’t feel like they would be much help. His arrived first. He brought the box upstairs, tore into it, and started lacing his skates. Two minutes later, he stood up in them and skated across the room. Pretty good for a guy in his fifties. Mine came two days later, long after all the rest of the safety gear had arrived. They are so much cooler in person! Traffic-stopping, knockout, glamorous roller skates. It’s entirely possible that they have magical powers. People cannot take their eyes off these things. Which is very good because otherwise they would be staring at me, flailing and windmilling my arms and wobbling everywhere at .5 mph. We carried our gear down to the alley that runs along our building, the same alley where our neighbors go to cry on the phone and smoke and have long dramatic conversations at top volume. Surely this alley can handle a couple of middle-aged people on wheels. There goes my husband, speed-skating, skating backward, practicing a variety of stops. Keep watching, I’ll eventually enter the frame, clomping along like a child playing dress-up in wooden clogs. We both realized something about ourselves in our first minutes on our new skates. My husband realized that his ankles are no longer as strong as they were when he was on an ice hockey team, before we got married. I realized that my core strength is basically gone and my balance isn’t so great either. I also realized, after about twenty minutes, that as much time as I spent on skates as a child, nobody had ever taught me how to brake. It suddenly occurred to me that the only way I had ever stopped myself when I was in motion was to grab onto something or crash into a wall. Traditional roller skates have a rubber stopper on each toe. Wait, you think I’m going to brake by tipping my foot forward until that thing touches the ground? Um, I think not. We practiced together, which meant he would skate backward while holding my hands so that I could practice going one direction down the alley. Then I would practice skating by myself while he made a couple of trips back and forth. It seemed like about time for us to pack it in. I had made a little progress and had an idea of what types of tutorial videos I might need to watch. Neither of us was bleeding or concussed. We changed back to regular shoes and headed upstairs. “That was good for a first day,” he said, which I heard as “first date.” It was! It was a pretty good date. A date on a skate with my mate. It’s spring, hooray! For me, it’s also been a year since I got COVID, and I’m starting to feel more normal. Ten years older, tired all the time, and still plagued with teenage-level skin problems, but other than that, more normal. Time to start thinking about working out again.

I’m starting to be able to do a full hour on the elliptical again without having sneezing fits for the rest of the evening. Only about 75% of what used to be a casual workout, but hey, it’s a start. It’s questionable whether this is the perfect workout, though. Research indicates that the body eventually adjusts to whatever it is that we do as the default, meaning that eventually, we quit gaining additional fitness benefits. In midlife, it’s not so much that we’re looking for Olympian levels of fitness. It’s more like staving off whatever aches or pains have been cropping up lately. Sadly, it’s probably more motivating to feel like “I can make this nagging pain go away” with some sort of stretch than it is to feel like “If I keep doing this, I can do some cool fitness tricks.” Make a list. Where does it hurt and when? All the time, or only when you stand up? Other than being in recovery from whatever the heck the coronavirus did to my innards, there are a few obvious issues I want to work on: Chronic neck and shoulder tension from working nine-hour days at a desk with poor ergonomics General stress level - the eyelid-twitching kind Twinges in one ankle, probably because I keep sitting on it while I work Now it’s time for another list, and that is: the constraints. Everyone has a list, probably mental, possibly engraved in marble, and that list is called Reasons I Must Be Let Off the Hook. “I can’t because.” Literally nobody cares - you don’t need reasons to do or not do things, just do what you want - but defensiveness causes us to catalogue our roadblocks and obstacles. (Downstairs neighbors, tiny living room, gym is closed, no equipment, etc etc). Meantime there is always someone in the world in the same situation, doing the thing we Cannot Do, because that person sees the thing as a reward and an entitlement rather than a chore or duty. And vice versa. For instance, nothing will stop me from reading for entertainment. I have a novel going at all times. I’ll read while I brush my teeth, put away groceries, fold laundry, or even while getting my teeth drilled at the dentist. There are probably people in the world who do not see reading as their escape and would not read during any of the times that I do. Therefore they’ll come up with their personal list of Reasons I’m Too Busy to Read. I would probably match most of the items on that list and use them as Reasons I’m Too Busy to... do nail art? Whatever else I don’t want to do that feels like social pressure. Anyway, it isn’t the “reasons” that we “can’t” do something. It’s the story we tell ourselves about what incentive we would have to do that thing. For instance, I won’t get up at 5:00 a.m. no matter how many productivity articles I read about how great it is. With two exceptions. I’ve done it in order to get to the airport for an international flight, because DUH, and I’ve done it in order to get downtown to run my one marathon. My mom got up with me to drive me, because she is that kind of person. Who would get up at five in the morning just to do something nice for someone. I, uh, would not do that. Let me give you the long list of reasons why I can’t give you a ride at 5:30 a.m., starting with “I don’t have a car” and ending with “I am not the kind of person who would wake up that early to do someone a favor.” We recognize our own inner resistance and often, we can laugh about it. One type of resistance is to hate the idea of doing anything trendy, and I have that big-time. I’ve never gone for a manicure, I don’t drink wine or coffee, I’ve never worn Crocs, and I’m darn well not going to do a popular workout just because millions of people enjoy it and find it effective. Or... maybe I can accept that doing what works is a good idea? This is where I turn to my practice of Do the Obvious. What would be the most obvious workout for someone with neck and shoulder tension? Yoga? Yeah, you’re probably right. What would be the most obvious workout for someone with high stress? Probably yoga again? Maybe. I actually have a different plan for that, and that is to draw on my natural preference for variety and dislike of routine. What if I just... chose a time slot and did whatever random workout seemed like fun to try that day? Dance, hula hoop, or whatever? As I was sitting here in the park working on this post, a hundred yards away there was a little girl doing cartwheels and various dance moves. She might have been ten or twelve. Never in my life have I been that agile. She hopped up on her bike and rode away, streamers blowing in the breeze, and I thought, I hope she has a fun summer. I also thought, I wonder if there’s still time for me. At 45. I wonder if there’s still time for me to learn to do a cartwheel like that? That’s how I want to feel when I work out, like a lithe and happy child playing just because she can. Rather than a lumpy, crooked office worker hunched over a desk, whingeing and twingeing her way into a crotchety retirement. It’s spring, and what will I do to enjoy it besides sit crunched up in my chair? The first time, I did it for money.

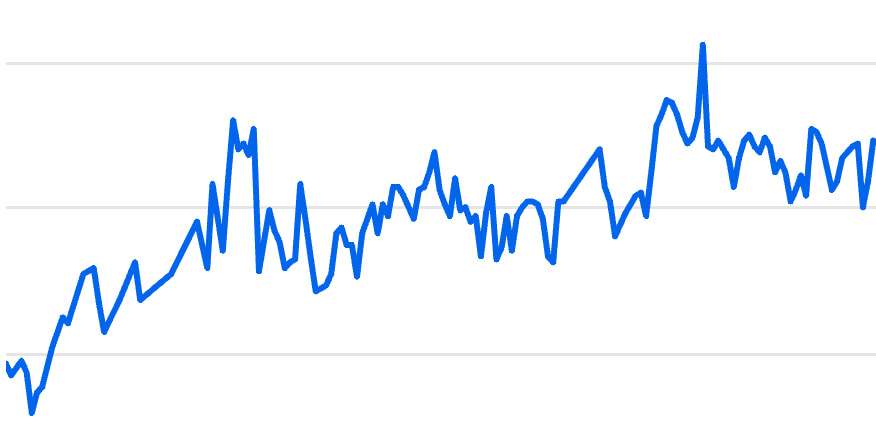

I was 29, I had just started my first full-time job after college, and I was flat broke. When I heard there was a contest at work with a pool of money involved, I didn’t care if it meant jumping off a roof or shaving off my eyebrows, I was getting that money. I didn’t think I was overweight; it was more like I didn’t mind potentially being underweight for a week or two if necessary. $100 was that valuable to me at the time. The truth was, I was obese and didn’t know it. I wound up losing 11 pounds in 3 months (not quite a pound a week), I got my cash, and I did it again a year later. I went from a size 14 to a size 6. During the time I worked at that place, I made something like $225 in these weight loss contests. Probably more importantly, I learned my way around a gym, built up my base fitness level, and started to understand how the bag of cookies in my desk drawer contributed to whether my pants fit or not. 2020 has been tough on me, partly because I almost died of COVID-19, and partly because my ego is crushed. This was going to be the year I turned around all the weight I gained in 2019. Instead I’m up 10 pounds from January 1st. On me - and I don’t know what it’s like on other people because I have only one body - on me, I can directly correlate extra body weight with migraine and night terrors. This was just as true when I was boxing four days a week and doing fifty burpees as it was when I was a size 14 and seeing black spots when I climbed a flight of stairs. I don’t know why this is. All I know is I don’t do well when my body weight hits a certain specific number. I have the intrinsic motivation to do whatever I can to regain my health in 2021. I thought, it’s the right time of year. What if I bring everyone else with me? A fitness contest was the first time I ever really took the initiative to do anything specific for my physical health. I was motivated by cold hard cash, and it worked. I visualized having to pay out $50, instead of receiving a payout, and every day that drove me to push a little harder. This is the only way that competition really works on me. If I can imagine a negative outcome on a specific date, I will work very hard to avoid that negative outcome. “I am not going to be that person” who has to pay $50 because I wouldn’t stop buying cookies to keep in my desk. Being the organizer of a contest is exactly that type of motivation that works on me. Imagine being the person who brought up the whole thing, and then publicly failing. I reached out to our human resources person to run the rules of the contest by her, the one that we had successfully done in the past. It had been fifteen years since I first heard about it, and I figured that the zeitgeist had probably changed since then. Better safe than sorry. I try to live by the rule NEVER GO VIRAL FOR THE WRONG REASONS, and part of that is to never come to the attention of HR for the wrong reasons either. The way the contest originally worked, everyone would weigh in once a week and a non-contestant would observe and record the weights. It was all private. Participants pledged $50 each, and the money went into a kitty. At the end of the 13 weeks, whoever didn’t make their goal forfeited their $50, and whoever made their goal split it. It usually worked out about 50/50, which tended to mean you either paid $50 or got someone else’s $50. The goal was to drop a percentage of your body weight in 13 weeks, same percent for everybody. I can’t remember what it was but I want to say 6%. If everyone made their goal, we would all just keep our money. If nobody made their goal, everyone had to pay up and the money would go to charity. Neither of those eventualities ever happened. It turned out that the pooling and splitting of the money was the problematic part. Possibly it touches on some kind of state law about raffles or sweepstakes. I had figured it would be more of a problem with the “weight loss” part, since apparently admitting that you want to lose 10 or 15 pounds makes you some kind of baby-eating demon. I had a plan for that part, though, because I still have every intention of running some kind of fitness challenge for 2021. It needs to result in me fitting back into my work pants, in case we start working on site again, or otherwise I will have to show up in my pajamas. The first place where I worked had an average employee age of around 53. There were several diabetics, and most people had the type of lifestyle-related health problems that are typical of people in their fifties. At this place, there is a much higher proportion of early-career people, including high school and college interns. There are more athletes; my boss recently took a meeting on his exercise bike. The majority of people who might be interested in a fitness challenge, then, don’t really have any weight to lose. What I’m proposing is much more complicated. Athletes all do different stuff, so how do you compare between, say, a swimmer and a power lifter? I’m aiming for total miles, total exercise minutes, and total weights moved across departments. This makes for a lot more metrics to track, but that also allows for more exploits, a nice feature of any game that draws people’s attention. How do I find a loophole so my team can win? My plan is to try to use this as a learning opportunity for myself. I want to learn to make different dashboards and data visualizations, and these are the type of numbers that I understand. If this all works out, it will give us something interesting to do during the final months of isolation. I’ll learn more about data science and hopefully fit back in my work wardrobe. Some people’s dogs will get out more. We’ll all feel more like a team. And anyone who doesn’t want to play can just ignore us. I’ll never forget the first time it rained after we moved to Southern California. I had tried running outdoors, and the air quality was so poor it made me wheeze. I gave up and decided that I would run on rainy days.

It finally happened. Not just a “thick mist” sort of rain, but a drenching downpour. I whooped and started getting my kit on. The dog followed me from room to room. He had about a hundred signals he could easily detect that indicated someone was going for a W or an R. (You couldn’t even use the words “walk” or “run” around him in any context, and then he started learning to spell, so we had to use initials). “It’s raining, bud, are you sure you want to go with me?” I opened the front door and showed him that it was raining just as hard out there as it was in the back. He signaled quite clearly that he wanted to go with me. We were both ready. It rained so hard that he had to stop once or twice every block just to shake himself. When we came home, all my layers were sopping wet, so wet I threw them in the tub. I gave the dog a rub-down with a thick towel, which made up for the soaking, and then I took a hot shower and put on dry clothes. An hour later, my husband came home to find us both bundled in blankets, poor Spike still visibly wet. “What happened here?” What happened was that I took advantage of weather conditions that most people in our region will avoid. I had the streets to myself. The reason this matters in this year of grace, 2020, is that there are still so many mask deniers out there. I live in a hot zone in the state with the highest case count. The statistics don’t phase my neighbors at all. Any time we leave our apartment, we pass more people without masks than people who are wearing them. It’s scary. I’m hoping that many of them are out to enjoy our “endless summer” for as long as it will last, and that they will then grump off inside over the “winter” to binge-watch something. That then it will be safe for me to exercise outside. There’s another reason I hope I can run in the rain this year, and that of course is that I am a COVID survivor. If I can run at all, ever again, it will be a miracle. Running is sort of what got me into this whole mess, but that’s okay. I forgive it. Going by the dates, I was exposed on March 15. I remained asymptomatic until the 31st, sixteen days later. I went for a run on the evening of the 30th, and that was my first real indication that anything might be a little off. Later that night I found out I was exposed. While I’m convinced that the exertion of that run is what tipped the balance for my immune system, I see being able to run again as a major victory over the virus that tried to kill me. In fact, if I go out again, I have every intention of running the exact same route I did that fateful day. I’ve done that before. Several years ago, we used to run in a regional park that was full of gloriously muddy and technical trails. I tripped over a rock, flew through the air, and landed on my face. Covered in bruises, bleeding, I limped home in torn pants. Did my first 5k a couple of days later. When I got home, I made a point of running that route over and over. Each time, I would shape my hand into a laser and “shoot” the rock that had tripped me. I recorded over the bad memory of that fall with dozens of uneventful trips, until finally I erased the anxiety that I had been feeling around that spot. It became my power spot. I would go up there and stand on the bad rock when I had tense phone calls to make or emails to send. I would get it over with, and then I would pause for a moment to appreciate the victory. There has been a lot of negativity directed towards runners during the pandemic, since apparently a lot of people have been out running with no mask on and they don’t distance from people. That is unfair and not how I roll at all. Honestly, when I see people coming I will sometimes go stand in some bushes or walk out in the road rather than pass near them. It ain’t me. I deserve to be able to run outdoors without being afraid of my mask-less neighbors, just like my neighbors deserve to be able to go for a walk without being afraid of me running up and breathing heavily on them. There’s plenty of room for all of us. The difference is, I’ve already been there. I’ve already been flattened by the coronavirus, and I was certain it was going to kill me, and yet somehow I lived when a million others did not. I know it’s real. I still have after-effects months later. Fortunately, the heart palpitations seem to have stopped. I almost never get hand tremors anymore, but I do sometimes when I’m very tired. The symptom that has hung on the longest is the weird thermostat problem. I still wake up shaking with cold probably once a week, even though the night-time lows have been in the high 60s. I will also start shaking with cold outside in temperatures where my husband is right beside me, sweating in shorts. I want to run just so I can feel warm again. It means a lot to feel like I’m starting to get well enough that maybe I could run a quarter-mile, like I tried to do on my very first day. I believe that COVID-19 damaged my heart. That scares me. There were several moments when I was ill and felt like I was moments away from having a heart attack or a stroke. There were a few times when I thought, I should probably call an ambulance, but then it passed. Something interior happens that you have never felt before, and a deep alarm system goes off. Yet running healed me, years ago, and I believe it can do it again. Obviously cells can grow, like we see every time we get a cut and it heals again. Just because there has been damage somewhere doesn’t mean it will never heal. Running helped heal my migraines and my night terrors. Running healed things I never knew it could. I hope I can run in the rain one day soon, and wave my arms over my head, because that will mean I still can. I’m sharing this as a COVID survivor, so if you insist on finding a way to associate my personal story with body image issues, I guess I can’t stop you, but that is not what this is about.

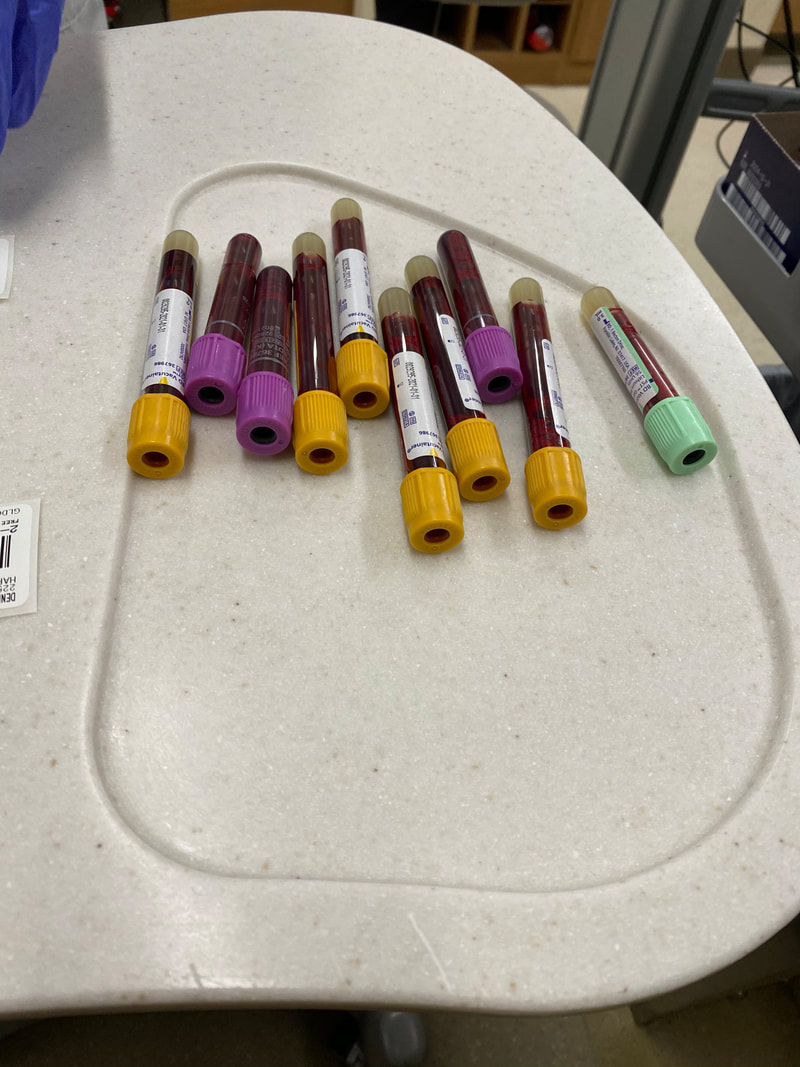

I started 2020 with the declaration that I was going to “get my body back.” At the time, I meant that I had gained weight and it was getting in my way. I had no idea that just a few months later I’d be fighting for my life, and that “getting my body back” would include the ability to walk across the room without hanging on to anything. Maybe some people can put on weight, and it’s mostly muscle, and it gives them power and vigor. I’m guessing. That was only ever the case for me for a couple of months out of my life, when I was training hard four days a week, right before I got my orange belts in Muay Thai and Krav Maga. I could do fifty burpees! Usually, on my body and in my life, extra weight represents fatigue and illness. One of those unfortunate signs has been respiratory issues. At one point I wound up coughing up blood, had to use an inhaler for months, and the nurses kept asking if I was sure I didn’t have asthma. (If I did, nobody told me). I was at least 30 pounds overweight back then. I made the connection when I was sick with COVID. I spent a lot of time feeling very low and mopey, very much in the mood to blame myself for everything I ever did wrong in my life, wondering how I had brought this on myself. (By going to stupid brunch, that’s how). It occurred to me to wonder if I would have remained asymptomatic if I hadn’t put this extra weight on in the past year. What the average healthy person does not feel is the sheer weight of having stuff on top of your lungs. It doesn’t matter what it is - a bag of flour, a book, a hefty cat, a pile of laundry, or an impressive pair of bazongas. When you’re having trouble breathing, you feel it. Your chest muscles start working much harder to get air into your lungs, and *shrug* weight-lifting is weight-lifting. Same with the throat. The single biggest risk factor for sleep apnea is neck circumference, and that is probably why it is common in professional football players. Big necks. Nobody ever says, Hey, if you drop some weight, your sleep apnea might go away, your asthma might improve. But they probably should. It makes me angry whenever I find out that a doctor has been withholding information from me that I could have used to make different choices. Anyway. I’m finally starting to feel well enough post-COVID that I decided to try to drop some of this extra weight again. I resisted Doing the Obvious, which I usually do because The Obvious is always annoying. Otherwise we’d all do it right away. In this case, I knew that keeping a food log was the only thing that ever helped me reach and stay at my goal weight. I did it for an entire year, and maintaining a steady weight was simple and easy. Then I figured I knew what I was doing, so I quit keeping the food log. Then I started boxing, and I would need a three-hour nap after training, and my husband said, “You need to eat more, babe, you’re putting on muscle.” Nobody ever needs to tell me twice that I need to eat more! Almost instantly I put on 15 pounds. Almost instantly, I started having health issues. Even as I was kicking butt (literally) in the mat room, working out harder than I ever had in my life, cranking out pushups like a teenage athlete, I started getting every cold and flu. Whatever I was doing, it was demonstrably not helping my immune system. What a food log would have revealed at the time was a series of double helpings of oatmeal, two-hander sandwiches, energy bars, oh, and, a lot of pizza and Mexican food and donuts. I’m not eating that way anymore; haven’t been since I quit the martial arts gym. As the months went by, I was stuck at a plateau and I couldn’t figure out why. Surely I eat sensibly! I had gained ten pounds since I contracted COVID and I had no idea why. It wasn’t like we were going anywhere. No travel, no restaurants. This is what I found out. It’s easy when you’ve done it before and you’ve learned the basics. It’s easy when you have a sincere desire to learn the truth and you know you are ready to make a change. That readiness usually comes out of frustration, annoyance, and maybe even a certain level of disgust with the current situation, such as: Why do I keep getting sick?? I was eating too much for breakfast. I was eating too much for lunch. I was eating an afternoon snack that I probably shouldn’t have been. I was eating too much for dinner. I was snacking too much on the weekend. There ya have it. Same story as last time. Eat 5% too much at every meal and any mammal will steadily gain weight. Will a hummingbird or an iguana do that? Not sure. I rolled my eyes, sighed passive-aggressively, and determined that I knew what to do. It’s straightforward when there is consistency across a day and across a week. I learned several years ago that it’s a lot easier to do body transformation if you eat basically the same things for breakfast, lunch, snacks, and beverages every day. I cut back the double helping at breakfast. I cut the afternoon snack. My hubby and I both agreed, since we take turns making dinner, to add in more greens and cut back a little on anything that is not green. I’m giving a side-eye to our weekend popcorn and what exactly goes into Fancy Breakfast, but I’d rather make adjustments on the five days than on the two days. Sure enough, I finally broke through the plateau that I’ve basically been stuck at since January. I was so excited that I jumped off the scale, my mouth hanging open. What, already?? Body transformation projects will be different for different people. Mine is mostly about my lived experience, my mood and my energy level and my health results. It’s somewhat about awareness. It’s also about bodily autonomy. This is my vehicle to do with as I will. When I pay more attention to what I’m doing in default mode, I like my results better. First off, I have to admit that I’m a total coward about donating blood. I tried to donate once, and I passed out when they did the finger stick, and they asked me not to come back “for several years.”

This is part of what helped me get through COVID-19. I had this fantasy that I would spiritually redeem myself by finally donating convalescent plasma, and the fantasy would help me fight my fear. But then reality hit. The first problem was how long it took to get better. When I first got sick, I thought I would go through hell for five days and then I’d basically be over it. I kept seeing pictures of doctors and nurses already back at work after they had it. Okay cool. Back in April, everyone believed that if you got COVID, you got immunity, and you were safe to go out and help other people who had it. Bless that. At least once an hour, I would comfort myself by thinking about how safe I would feel once I got better. I’d think about how I could leave our apartment. I’d think about helping other sick people. I’d actually make myself cry, picturing myself doing someone else’s laundry and bringing them soup. When I thought about donating plasma and potentially helping four people at once, it about did me in. I really, really wanted all that to happen. It gave me hope like nothing else. To think: there could be a little army of healthy people helping everyone pull through. But then it just kept dragging on and on and on. I was sick for weeks, and I felt like I was truly dying, and when I got through the gate I was really just a shell of my former self. Quite honestly, almost six months later I still haven’t made it past 85%, and that was only for a couple of weeks. I am still occasionally waking in the middle of the night shaking with cold, even under a duvet with a nighttime low of 68 F. My eyelid is still twitching and sometimes my hands still tremble when I’m tired. Sometimes my heart still pounds for no obvious reason. I still planned to do it, though. I was still totally going to go in and donate convalescent plasma. I wanted to help people, and I wanted to confront my demons. I also figured it would be the best way to get an antibody test. My husband is still uncertain about whether he really got exposed or not, which makes him worried for himself, and he’d really like to get his antibodies checked too. He has donated plasma before, because unlike me he is quite brave, so that part doesn’t bother him. We were going to go in as a team. I did some checking. I found that there were a few different places where we could donate. We could also donate our data and be part of various health studies. Then it turned out there were some rules. The first was that you are supposed to have tested positive for COVID-19. I wasn’t sure about that one, because I was diagnosed as presumptive positive but I wasn’t able to get a test before I had cleared the infection. Of course my plasma would be valuable under any circumstances, so it was still a good idea to donate. Then there was a rule that you couldn’t have any medication in your system. I was on antibiotics for the opportunistic bacterial infection that attacked me just as I was clearing COVID. Definitely would have to wait until that was gone. Then they wanted 30 days with no symptoms. (Now I think it’s 14). That’s what wound up doing me in. I just couldn’t get there. As a matter of fact, I haven’t yet made it a week without some weird health issue or other. What it comes down to is that I don’t think whatever is or is not in my blood would necessarily help someone else’s immunity. It doesn’t seem to be doing me all that much good! I’m lucky in most ways. I just turned 45 - that’s it, that’s the tweet - and I’m doing all right. I still have 20/20 vision. My cholesterol is 150 and my blood pressure, blood glucose, etc are all right on target. I’m graced with a cast-iron stomach and decades of reliable digestion. My doctor (before COVID) told me, “Whatever you’re doing, keep doing it.” It’s just that, between March and May 2020, I suddenly started having heart palpitations and serious concerns that I might be having a stroke. Now, I believe in my body’s innate capacity to heal. Every time I watch a cut gradually fade away I marvel at it all over again. I even cut my eyeball a couple years back, and that healed within days. Just because a virus played Pac-Man in my cells does not mean the damage is permanent. I believe it takes time, rest and sleep and lots of water and cruciferous vegetables. (And antibiotics and modern pharma, as advised by a mainstream medical professional). Alas, though, I don’t think I am healing fast enough for my convalescent plasma to be all that useful. There is still a lot of research to be done on this as a treatment, believe it or not, even after a century of speculation and trials. It looks like there is a limited time window, though, for a recovering person’s blood to contain the magic of convalescent plasma. Also I am still recovering from the case of pneumonia that I got for my birthday. I mean seriously. I’m not sure whether this saga will ever end. I’d rather that my life is no longer defined by a stupid, pointless disease that I contracted in the dumbest possible way. It’s making me focus inward and inward, trying to heal myself and get myself back to normal, which is boring in the extreme. There is nothing nearly as satisfying in “self-care” as there is in the selfless care for others in need. Are you braver than I am? Are you tough enough to have a nurse put a little needle in your finger without fainting dead away? Do you have it in you to share that much of yourself? If so, I envy you, and I feel really small in comparison. It haunts me that nothing I will ever do will be quite as charitable as donating blood. I wish that I can be strong enough to try it again one day. In the meantime, maybe someone with a big heart will think of me and make the call, do the thing that I can’t yet do. Save someone’s life, maybe. Long-winded, some might say. I was always a person who could go on and on, talking into the space until it was full. I think I’ve demonstrated that I can talk continuously for 24 hours, and if you’ve ever been on a road trip with me then you’re probably nodding right now.

Not long-winded anymore. A couple years ago, when I was working on public speaking, I had a real issue with talking too fast. My big goal was to work on pausing. Every evaluator I had would suggest the same thing, so I knew it would be valuable. I just couldn’t train myself to do it. Since COVID and pneumonia, guess what? Now I can pause. I mean, I have to. But also I can. One of the many weird after-effects of this year, which has been so tough on my body, is that it seems to have lowered the register of my voice. It sounds deeper to me. I also notice that I speak more slowly and that I pause all the time. What was a virus that is no longer detectable in my body - two negative tests so far - has wreaked permanent havoc. I do wonder, though, whether all of the changes are negative. What if this experience has given me the gravitas I always wanted? I was always small for my age, always looked younger, and I thought I would always have a high, small voice. This undoubtedly held me back in my career. Now I’m 45 and I probably do look my age. I no longer sound like a teenage girl. Maybe this will be good for me. Of course there’s the undeniable gravitas of facing death, of living through an experience that many people find... qualifying. (It turns out that most transformative experiences don’t actually impress people. Either they don’t care, they think you’re whining, they don’t believe you at all, or they don’t understand enough of your situation to realize it matters). I had a minor nature encounter, back during my first marriage. I smelled and heard a little bobcat while walking in the woods in the pitch dark. It screamed and then I screamed. Activated my limbic system in a big way. I told the story during a safety presentation at work, and I realized partway in that every single person in the room thought I was totally full of it. Now, a bobcat weighs less than 20 pounds, like a medium-sized dog, and there are around three million of them in Oregon. For a person like myself who is comfortable in the backwoods, this was a fairly casual anecdote. I wasn’t claiming I raised one from a cub, or that it attacked me and scarred up my throat. I wasn’t even claiming I had seen it! The point of my story was that I was scared senseless, which I thought made me sound like a loser, or at least appropriately humble. Instead, it appeared I had made myself look like a BS artist. Oh well. It’s probably going to wind up being the same thing with COVID. Most people who get it will either never know (that they spread it to someone who died) or will be super sick for a few days. Maybe only about 20% will be in my tranche, of people who felt like they were dying but managed to stay out of the hospital. What, no ventilator? No coma? No amputations? No seizures? Pfft. And you call yourself an invalid. That’s pronounced INvalid, not inVALid... I took out the trash just now, and when I came back, I flopped back into the couch, huffing and puffing like a pregnant walrus. My husband looked up from his book. “You made it!” Then he checked my pulse. The truth is that I’m still struggling. Most of my lingering symptoms are super dumb, petty annoyances that really don't count in the grand scheme of things. Yet I wonder if, cumulatively, they might add up to a list of things that a young person might find repulsive enough to avoid? The twitching eyelid - my left eyelid has been twitching for weeks. Will it ever stop? Dunno. The breakouts - the return of my teenage bad skin. It hasn’t been this bad in 25 years. Compared to the heart palpitations, this is truly nothing, but a 20-year-old might actually care about the boil on my chin or the chest acne. Put your mask on honey. This, you don’t want to happen to you. The weight gain - yeah, everyone else gained weight eating all that nice sourdough bread during the first months of staying home. I can barely get my pants to zip. Now a ten-minute trip to the parking garage to take out the trash is my new “distance day.” I sincerely have no idea whether I’ll ever be able to work out again. I’ve barely moved in four months and all my boxing muscle has withered away. The constant sneezing, runny nose, coughing - goodbye romantic life. It’s hard to imagine anything less sexy than a dripping nose, am I right? The way I’ve become a crashing bore - every topic and every conversation seems to turn back to being ill, or the pandemic, or symptoms, or something COVID- or pneumonia-related. This is why young people avoid elderly people, and it’s also what makes someone “elderly.” Not that long ago, I was a person who would run up the stairs two at a time. I would do box jumps at the park. You have no idea how many hula hoop tricks I know. In my heart and mind, I am still young and interesting, only now my body is ravaged and lumpy and full of boring things. I’d say I can’t bear it, but I can. I have to. I’ve been bearing it so far. COVID ruined my life. Ruined it. Everything I think of as what makes me myself is not really an option. Can’t travel, can’t go backpacking, can’t go for a run, can’t throw dinner parties, can’t be with my family - most of this applies to everyone - but I also can’t fuss around cleaning my apartment for more than a few minutes a day. Haven’t yet figured out how to make a path for writing or public speaking the way I had planned. Not sleeping well. Can’t even “take a deep breath and relax” because I can’t do the first part anymore and rediscovering that each day is not relaxing whatsoever. What’s needed is to come up with a new story. Maybe not a long-winded story, not one that is full of detail, but something. A story in a nutshell. A thumbnail sketch. A haiku of a story. We can’t always talk our way out of things, but maybe we can at least imagine our way out. I ordered some breathing apparatuses and they were delivered today. As a COVID-19 survivor who is currently trying to recover from bacterial pneumonia, I want to improve my breathing. Like, a lot. I’m starting from a knowledge base of zero and trying to figure it out as I go. What are these things, how do they work, and can I actually start breathing normally again one day?

The first thing I can tell you is that if I get arrested in the near future, it will be because a police officer saw one of these things and assumed it was a weird futuristic vaping tool. I can about guarantee that an airport security guard somewhere in the world would confiscate it. I want to put a tag on it that says ‘NOT DRUG PARAPHERNALIA.’ The other thing looks and acts like a children’s toy. Actually they both look like children’s toys, in their own way, which is great because I can use some fun in my life. Relaxation techniques always tell you to focus on your breathing because they assume that is universally relaxing. I’m here to tell you that it would be more relaxing if I could stop focusing on my breathing for a while. It shouldn’t take this much effort. It shouldn’t be in question. I shouldn’t be wondering so much about how long I’ll be doing it or if I’ll accidentally quit while I’m asleep. I first learned about breathing exercises as a tiny tot, when my mom was in labor with my brother. I remember I kept trying to lean over the seat and help her do her Lamaze breathing, and my dad kept snapping at me to sit down. (We didn’t have car seats in those days). I associated special breathing with the magic of a new baby popping into existence. The next time was in kundalini class in college, but that’s a story for another time. I had a less exciting lesson in breathing when I got the respiratory infection that followed me out of university. A nurse had me breathe into a spirometer to measure my lung capacity (52%). This memory is what gave me the idea to buy a device of my own, and that’s what triggered the idea that I could find a gadget to measure my improvement. The device that the nurse used on me had me exhale as hard as I could into a tube. Apparently what she was measuring was Forced Vital Capacity. When I found out about incentive spirometers, this is what I thought I was getting. The device I bought (for $9 US) has you inhale through the tube as slowly as you can while trying to keep a little ball suspended in a tube. It’s the exact opposite of what I thought. What I was hoping for was a percentage capacity measurement like I had 16 years ago. For one, I wanted to compare it to how I measured when I was younger. For another, I wanted a baseline. I’ll admit, though, partly I wanted to show off just what bad a shape I’ve been in. What I’ve learned, while scouring the internet, is that I would need a trained nurse to do this properly. I can’t really make any official medical claims because I don’t have the proper training and because I don’t even know where to find the correct device, which I might not be able to afford. All I can do are three things. I can start with a baseline; I can train and compare my later results with this baseline; and I can compare myself with my friendly local husband. (I had him test everything out before I put my mouth on it. I’m not great at reading instructions at the best of times and he happens to be an engineer). We both tried the incentive spirometer. After we figured out how it’s supposed to work, and by ‘we’ I mean ‘he,’ we timed each other. Then he did the calculations. He was able to keep two of the three balls in the air for 9 seconds. (The third ball isn’t supposed to go up). I was able to keep the first ball in the air for 3 seconds on the first try, and 4 seconds on the second try. No second ball. My head was spinning afterward. I’m super competitive about this stuff, though. Ordinarily I have the attention span of a... sorry, ran out of analogies. But when I’m fixated on something, I’m like one of those squirrels that never quits going after the supposedly ‘squirrel-proof’ bird feeder. There is now no way I will quit practicing with the incentive spirometer until I can keep the ball up for 10 seconds. What the times supposedly mean, if we have any even remotely accurate idea of what we’re doing, is that my lung capacity is like 2400 CCs and his is like 5400. The trouble is that we have no idea what’s normal. Also, he is a tall man with a large build, a lifelong athlete who joined the swim team at age 4 and who also played the tuba. I, on the other hand, am of average height with a small frame. I had COVID-19 all through April and I’ve been fighting pneumonia for a week. The other device that I bought is a special breathing trainer that has apparently been in use since 1980. I can tell you right now, if this was designed in the late Seventies then there’s about 100% chance it was inspired by a hash pipe. Me: “Do you think you could make this into a bong?” Him: [glances over] “It is a bong.” Note: We are straight-edge people by inclination and by profession, and also we plan to retire early so we save our money. But also we live at the beach and that kind of thing is recreationally legal here. The “Breather,” as it is known, now comes with an app and a training plan. I set it up, but for some mysterious reason it gave me today as an off day, so I don’t know what the exercises are like yet. All I know is that it believes age, height, weight, and gender are relevant. Well, that, and the positive reviews included athletes as well as people with various medical issues. I’m a diligent person. It makes sense to me to follow medical advice, especially when I paid for it and took time out of my schedule to hear it. I’m the kind of person who carries dental floss in my purse. (Right next to the Blow Pop, the dog clicker, and whatever else I have in there...) I have the patience and the persistence to sit down with these new gadgets and test myself, day after day. Because if the alternative is to keep being as short of breath as I am today, almost anything is worth trying. Here’s a little bit of hope for the tired people, the injured, the ill. It can get better. Little by little, it can.

I started recovering from COVID-19 about six weeks ago. I’m back to working out, doing 60 minutes of cardio a day. It feels great! I just realized today that I couldn’t remember the last time I had vertigo. That was a symptom that lingered for so long, I sort of thought I might just have it for the rest of my life. I figured every time I rolled over in bed, the room would spin, and I’d just have to get used to it. Then, finally, it went away. It’s important to notice these small victories, because it’s very easy to start believing in illness and injury as permanent conditions. The body doesn’t just “get stuck that way.” Sometimes it takes surgical intervention, sometimes it takes prescriptions, sometimes it takes many months of physical therapy. But the body can change and heal. That’s what a body does. I keep thinking of this as I watch my surgical scar heal. It’s almost completely invisible now, thanks to my obsessive twice-daily slathering with scar cream. What I thought would be a large ugly mark in an unfortunate location is now basically gone six months later. In fact, it looks so good that I’m going to take a picture of it and email it to my surgeon, a nice side-by-side before/after for her records. Satisfaction of a job well done, that is one thing that never goes stale. Yep, it’s been a rough few months. First the surgery, then COVID. I might also mention that I had quit running several years ago because of an overuse injury to my ankle. Year after year, month after month, there always seems to be a good excuse to roll over and quit. Legit doctor’s notes! This isn’t P.E. though. I don’t have a desperate desire to escape gym class any more; now it’s more the opposite. Let me back in! What do I need to do today to make my body feel at least marginally better? For me it revolves around quality of sleep. No matter what else is going on, if I’ve slept poorly I feel terrible. I believe that sleep is the main factor for a strong immune system. As a recent COVID survivor, this is understandably high on my list of priorities. Sleep depends on a few things, which are also very important to me as a person with a parasomnia disorder. (Yeah, I didn’t really appreciate having night terrors WHILE I was sick with the coronavirus, as if I didn’t have enough problems). These things are meal timing, hydration, and cardio. For night terrors, the absolute most important factor is to stop eating three hours before bedtime. I front-load my calories for the day, making an effort to eat about 3/4 of my fuel by the afternoon. Parents of tiny kids should note this, because night terrors are common in kids and they often get a bedtime snack. I think those things are related. Hydration is shockingly under-rated for insomniacs. I’ve found that if I’m even a single glass of water short for the day, I just can’t drop off. My sleep quality is dismal. I use an app to track my fluid intake, which is admittedly very boring, but not as boring as lying awake in the middle of the night for hours. I’ve tried out a bunch of different types of exercise, and they are good for different reasons, but in my experience cardio is the best for mood elevation, pain management, and sleep quality. When I can’t do it for a while, due to schedule, injury, or a cough or whatever, I start to feel the difference within days. There are different types of peace available from other types of workout; for instance, martial arts somehow magically removed my fear of needles and yoga is great for releasing old emotional junk. They just don’t hit the same physiological targets as running, biking, or the elliptical. It is so good to be back to reconsidering my workout! In April, I felt like I was dying. Now it’s mid-June and I don’t constantly think about being ill anymore. I put some effort into small improvements, in a process that is known as the “aggregation of marginal gains.” If you improve something by 5-10%, it may be enough to make a disproportionate difference in your results. For instance, 5% of one hour is three minutes. Getting ready three minutes earlier could be enough to start being on time for most things instead of chronically late. Cutting spending by 5%, as another example, could make the difference between being in debt or financial freedom. Little things can add up quickly. My small improvements in recovery were: Increasing our intake of cruciferous vegetables Tracking my fluid intake Setting a bedtime alarm Arguably, starting to work out again was not a small improvement but rather a “keystone habit.” It does tend to make the other steps, (drinking more water and going to bed earlier) just that little bit more attractive. More sleep. Better quality of nutrition. More water. Hard to argue with this strategy, two parts of which are free of charge. Right now it’s hard to tell whether my mood has improved so much just because I’m getting well, or because I’m something of a cardio junkie. Does it matter, though? Right now, I have everything I wish I did when I thought I was on my deathbed: my new dream job, the ability to do the laundry without tipping over and crying, maybe even the chance to run an ultramarathon in a few years. It’s so hard to be seriously ill and feel like it will last forever. It’s so depressing and boring and lonely and exhausting and painful. Every day we’re still here to complain, though, is another day we’ve made it through. Every day is one day closer to feeling better. One day, maybe even so much better that it didn’t even seem possible. Most of us are probably feeling it, the tangible levels of tension and dread. The restless sleep. The bizarre dreams and outright nightmares.

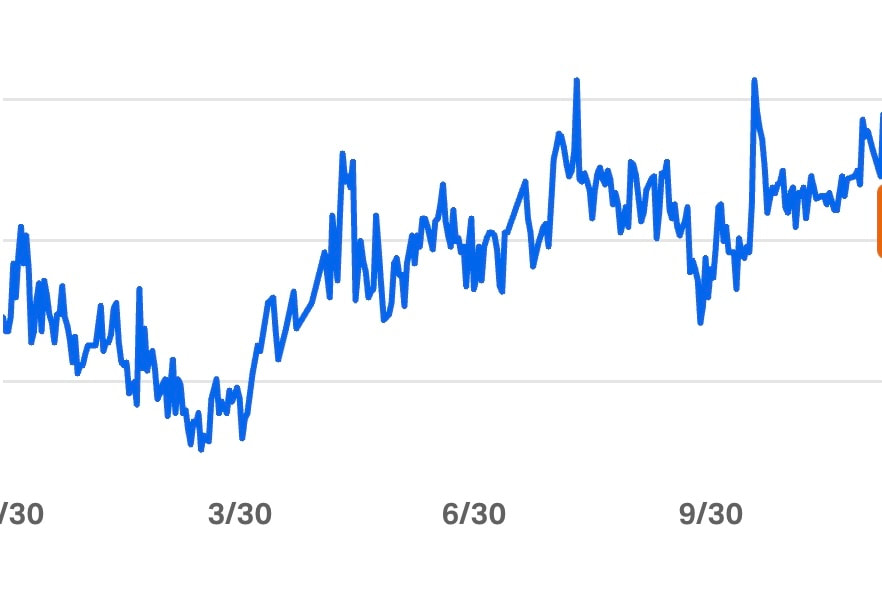

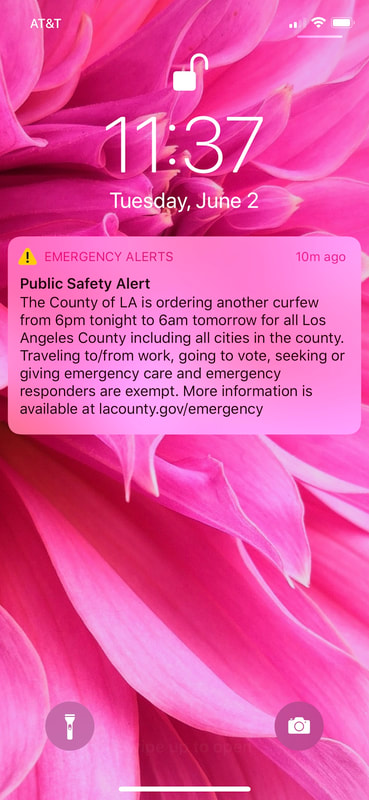

These are the reasons I run. Or used to, before the last time I went out and ran myself into a full-blown case of COVID-19. I’m still recovering, still not totally feeling normal, still having trouble with concentration and focus sometimes. External events are obviously a bigger deal than my private little hassles. Still they are real to me. We all work with what we’ve got. I’ve been trying to rebuild my base level of fitness on a cheap, clunky, creaky elliptical machine next to my bed. I skipped a day, and I paid for it. Wandering around all day with that anxious feeling in the belly, that tax-audit, principal’s office, performance review, collections agency, uhoh Dad’s mad feeling. That Sirens all day Running feet and panting breath in alley below our apartment Protestors marching within a mile of us Helicopters, sirens, helicopters I smell smoke, where is it coming from?? What the heck is going on, will it ever stop What can I personally do Feeling. Sometimes it isn’t clear at all what you can personally do in a situation. Sometimes it takes time to figure out. Sometimes it’s better to stay out of the way. Sometimes you realize you’re in someone else’s movie, and not only are you not the star, you’re not even an extra, in fact you’re blocking the shot. Other times, it’s clear that it’s your time to step up, because you’re the one who is accountable, or you are the only person who can really fix something. Either way, it doesn’t help anyone to have a toxic stew of stress chemicals burning you up from the inside. Burnout is largely physical. We have to pace ourselves, and the more that is on the line, the more important it is... yet paradoxically, the harder it is. The same predictable things happen every time, when we aren’t sleeping, we don’t have enough down time, we aren’t eating right and we have no way of dumping all that cortisol. Our sleep is disturbed even more We lose patience We get snappy, irritable, and mean We feel weepy and we’re not always sure why (except when we are) We can’t think straight We get spun up over even minor decisions Something that is the same in martial arts training and in leadership is a thing called “stress inoculation.” It’s possible to gradually train out the stress response in your body, so that you don’t react the same way even in the most intense conditions. In both roles, you take ownership of yourself as first responder and chief decider. Nobody is coming and it’s your problem to figure out. There is no more time and the moment is now. Some of this comes from having a plan. Some of it comes from having a formally acknowledged title and clearly defined responsibilities. Some of it is just that training in managing the physical stress response. After a while, you feel it. You can feel the difference between when your neurochemicals are messing with you and creating the artificial sense of a real problem, or an actual real problem. For some of us, a crisis is actually less stressful, because it’s obvious what to do. There is a specific issue that might actually go away if the right steps are taken. All this physical anxiety is *for* something. I felt that way when my husband badly hurt his eye and I needed to get him to the hospital. Weirdly, I’ve also felt this way during the stay-at-home order, and again when I got COVID. “Just get through this, nothing else matters right now.” Right now, three days into a riot-induced countywide curfew, I have no idea what to do. So I do what I always do when I don’t have a plan, which is to try to run it off. Five miles a day, miles of nowhere, going yet more nowhere. It feels like a metaphor for life right now. Perpetual motion, tension, stress, with no end in sight and nothing to show for it. Like a hamster on a wheel. For now, at least, the ball of tension is gone. I can chill for an hour or two. Later tonight, sure, I’ll probably wake myself up every two hours. I’ve been having social distancing nightmares - have you? - including walking down the street six feet apart with my ex-husband, and accidentally bumping into the Plandemic lady on the sidewalk. (We both went UGH). This is in addition to the COVID nightmares - fighting a twelve-foot spider with fireplace tools in each hand, millipedes crawling out of my veins, downloading the virus by wi-fi into all our electronics. The sleeping nightmares and the waking nightmares. With all this going on, it’s easy to lose sight of how great it is that I can already do five miles on the elliptical. I survived! I lived through a month of coronavirus and I’m getting my body back! Reclaiming my flesh and staking ownership of myself. In the midst of everything else, I can hit pause for an hour. I can try to get back into my body. I can try to remember that it’s the only vehicle I have to navigate this dumb old world. It isn’t wrong to center yourself, or to sleep, or to do whatever you need to do to restore your focus. There are still 16 or 23 hours a day to worry about everything else. World events will keep happening, whatever they are, for good or ill. One of the few things you can control is your interior ability to cope with things. |

AuthorI've been working with chronic disorganization, squalor, and hoarding for over 20 years. I'm also a marathon runner who was diagnosed with fibromyalgia and thyroid disease 17 years ago. This website uses marketing and tracking technologies. Opting out of this will opt you out of all cookies, except for those needed to run the website. Note that some products may not work as well without tracking cookies. Opt Out of CookiesArchives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed