|

I went for a run. Well, sort of.

Whenever I am grieving something, I try to work it out physically. Most likely I will go around cleaning things and reorganizing closets. Or I will try to run it off. The last major loss that I had to grieve happened when I was still doing martial arts, and I was able to ask my training partner to put some extra heat on the pad during Thai sit-ups. That’s really what I want right now, for someone to repeatedly smack me in the belly with a large heavy pad and try to knock the wind out of me. Mood. I had to drop off the loaner birdcage that we wound up with during the first emergency run to the veterinary hospital. We also had a pending bill. During normal times, this would be a routine errand. Given the circumstances, a massive dark cloud of sadness surrounded that entire corner of the dining room. I had to do the thing I could not bear to do, and it was miserable, and there was never going to be a good time for it, and so I pulled my socks up and prepared to do it. Then I had an idea. The old me popped her head up from the primordial ooze where she had been hiding. What if I went there and ran back? The last time I went for a run was the day I discovered that I had caught the coronavirus. Not a great association. There was one more issue. I happened to have blown out my only pair of running shoes on my recent hike. I had been tossing around the idea of trying to run again, just to test out my lungs and find out how much damage I had sustained. All the pieces fit together. I could take a ride share to REI across town, drop off the birdcage on the way, and then run/walk back. I knew I could walk that far, so even if I couldn’t manage to jog more than a couple of steps, I had enough time to walk home before sunset. These are important parts of the planning for new or returning runners: What are you going to wear? Where are you going to go? What is your fall-back plan if something goes wrong? I ran and hiked for years before almost dying of COVID-19. I had hundreds of outings to test every possible combination of gear and clothing in every weather condition. I already knew how to monitor my hydration and glucose level. In some ways, this was a serious problem, because I had intellectual expectations of what my body could do without information about whether any of that was still true in my new, janked-up form. A lot of middle-aged people still think of themselves as athletes, because they were athletic in their teens and twenties. Maybe more time has passed than they realize. It can be a real blow to the ego to discover that your cardio endurance capacity has decreased. My advice would be to lower your expectations and think of yourself as the same fitness level as your least-fit age cohort. Then you can instead be pleasantly surprised at your strength and agility. The first thing I did, once I had my plan, was figure out what to wear. I would be going in the door without running shoes, and coming out wearing a new pair I had never seen before. I also needed to think about what I would want with me on the return trip. Nothing about my plan would work for the combination of sundress, sandals, and purse that I wore to the dentist earlier that day. I chose my larger hydration pack, standard workout clothes, and sandals. I packed a pair of workout socks. These preferences are highly individual - there is no one correct answer; it depends on the person’s build, the climate in their area, and what type of workout they do. I went through several brands of socks before settling on the ankle socks that I wear now. I have workout leggings chosen mainly because they don’t have exposed elastic in the waistband. It took me about five minutes to pick out running shoes. This is because I talked to a trainer after blowing out my ankle, and he told me I should give up my barefoot shoe style (thin sole) in favor of a “neutral shoe,” which are in my opinion enormous, heavy, and hideously ugly. I have a couple of preferred brands - Brooks and Merrells - that work for my shape of foot, which is narrow with a high arch. It was basically: “Hi, I’m looking for a neutral running shoe, can I try that in an 8?” I jogged around the store for 30 seconds, put my sandals back on, bought the shoes and an energy bar, and left. I walked down the road while eating the energy bar. It was the hottest part of the afternoon and I had not brought any water, despite the fact that I was wearing a hydration pack, because I don’t always do smart things. I opened my old running app, only to realize I had forgotten my login and password. This used to be something I did four or five days a week, and now I wasn’t even 100% certain I had the right app. I managed to jog along for a quarter mile before I felt like I couldn’t do it any more. I had a stitch in my side and I was just completely out of breath. I slowed to a walk, which was fine. I was listening to a podcast, and I knew where I was going, and I actually liked the new shoes. (Brooks Ghost) Some distance went by, and I caught my breath, and there was a downhill slope in the shade. I worked up to a jog again. For a trip slightly over 3 miles, which is a 5k, I probably jogged close to a mile and walked the rest. I did most of the downhills. When I came home, I was absurdly tired. I could barely get up the stairs in front of our building. I pounded a liter of water. That night I slept over ten hours. The first day I decided to try running, I couldn’t make it around the block. I was not able to jog a distance of a quarter-mile. Not quite ten years later, after a moderate case of COVID-19 and a follow-up case of bacterial pneumonia, I did better than that. I had no heart palpitations. I did not pass out. I did not wheeze. I did not have to stop to lean on anything or sit on the ground. I didn’t have to call a ride share to get me home. Part of me is sad that I can no longer complete a 5k without having to walk most of it. The other part of me is thrilled that I was able to do a 5k and actually jog part of it! Also I want to state very clearly that until I got my COVID-19 vaccine, I was pretty sure I would never run again. My symptoms dragged on for a year, and it was only after being fully vaccinated that I started to feel like I could get out there again. When I first began my running journey, I was in worse shape than I am now. My cardio endurance at one point was so poor that I would see black spots when I walked up a single flight of stairs. I know that I have the self-discipline and grit and determination to drag myself up from a lower point than I am at today. How long will it take before I can run a 5k again without stopping? I have no idea, but I am going to find out. This is what is going on with me.

I got both my vaccines, and then I traveled for the first time in a year and a half. I went to three different international airports and sat next to strangers on two separate planes. Both flights were full. I’ve been running up the stairs. All I can do is speak to my own experience, and that is that the COVID-19 vaccine seems to have restored my health. I spent a year dealing with long-haul COVID symptoms, and now they are gone. Now I’m idly shopping for new running shoes. I’m tentatively thinking about short hiking trips. I’m feeling my way back into what used to be a pretty active, outdoorsy lifestyle. This isn’t just a personal anecdote. I know that millions of people, for some reason or other, are petrified about vaccines. It feels really important to share that vaccines work and that they are safe, routine, and normal. I’m starting to get the sense that getting vaccinated - against anything, really - may have a way of making a naive, “all-natural” immune system a little smarter and more efficient. I’ve been vaccinated against, let’s see: measles, mumps, rubella, tetanus, diphtheria, whooping cough, hepatitis A & B, influenza, and now COVID-19. There are probably others that I have forgotten about - but apparently my immune system has not. What is important to me here is that I never got sick with any of the things I was vaccinated against! I had the misfortune of contracting coronavirus early in the pandemic. The day I was exposed there were only 3,000 recorded cases in the US. Obviously there wasn’t a vaccine available yet. If there was, I would have lined up to get one, because I get the flu shot, too. For some reason, a lot of people are suspicious of the testing around vaccines when they are not equally suspicious about other things. A few that come to mind are the cumulative effects of food additives across products and across time, and whether the ingredients on the label of “supplements” actually match what is in the product. I know someone who believes she doesn’t need the vaccine because she drinks a tablespoon of apple cider vinegar every day. I know several people who are adamantly against vaccines but who will use “supplements” and essential oils with wild abandon. Question: why do you trust the makers of these products so fully? Why don’t you demand the testing on these products that you do for vaccines - or can you even explain what kind of testing you would want? How do you know that isn’t already happening - is this a close scrutiny or an intuitive rejection? The problem with taking a firm, documented stand for or against a certain lifestyle is how to rebrand your position if you wind up having a health problem. I didn’t have time to formulate some kind of claim about whether I thought I could keep myself from getting sick with COVID. I got infected before I really had time to realize that hey, this could happen to me. If I had had more time to gather my dread and anxiety, as more people in my community started getting sick, I probably would have figured, yeah, I do tend to be vulnerable to respiratory infections. If I got it, I would probably be in trouble. There doesn’t seem to be any profit to me in making claims that can easily be refuted. Maybe I say something like, Oh, I eat a lot of cabbage, you should eat cabbage too so you don’t get sick. Then I get sick. Oops. Health is like religion for a lot of people. The way we deal with our anxieties is to build some sort of belief system that helps make sense out of a weird and frightening world. It helps us feel like we have some control. I bought this consumer product from a skilled marketer! It’s called [x] and the packaging looks like [y]! Owning this makes me feel strong, smart, and confident. If I can convince you to buy it, too, it will reinforce my feeling that I know what I’m doing. I did it, too. I bought some expensive vitamins that I took while I was sick. I got better. Was it because of these vitamins, or would I have gotten better anyway? Was I getting better anyway, and maybe... *gasp* ... the vitamins actually interfered with my healing?? There is no way to explore this counterfactual because I can’t go back in time and do it the other way, as a control. I can only guess and hope I’m right. This is why I look to big data and studies and testing done by other people. I don’t necessarily know the full resume of every one of these people - but I do know that I cannot trust myself as a single point of data. I’ve tried, and it’s stressful and confusing. What I do know is that coronavirus made me very ill, even though I am a not-old person who lacks a single one of the comorbidities on the list of risk factors. At least there is no question in my mind whether COVID is real. What I know now is that it’s possible to get better. That process will probably be shorter for some people and longer for others. Does this apply to other illnesses that are not viral? I don’t know. I only know what I experienced. Right now, I am finding that my energy level is getting better and better. I am starting to have the urge to move faster. This includes running up flights of stairs. A year ago, I could barely get down a flight of stairs, even clinging to the railing, without shaking, sweating, and waves of nausea. Physical recovery has a lot in common with adjusting your mental framework. It can make you want to just lie down and take a nap. It can involve a lot of brain fog. It can feel like running upstairs, working so hard just to get to a higher level. Bodies and minds are both designed for growth and movement. Both need to be exercised to function as well as possible. Exploring different ways to respond to a problem is nothing that we can’t handle. I’ll never forget the first time it rained after we moved to Southern California. I had tried running outdoors, and the air quality was so poor it made me wheeze. I gave up and decided that I would run on rainy days.

It finally happened. Not just a “thick mist” sort of rain, but a drenching downpour. I whooped and started getting my kit on. The dog followed me from room to room. He had about a hundred signals he could easily detect that indicated someone was going for a W or an R. (You couldn’t even use the words “walk” or “run” around him in any context, and then he started learning to spell, so we had to use initials). “It’s raining, bud, are you sure you want to go with me?” I opened the front door and showed him that it was raining just as hard out there as it was in the back. He signaled quite clearly that he wanted to go with me. We were both ready. It rained so hard that he had to stop once or twice every block just to shake himself. When we came home, all my layers were sopping wet, so wet I threw them in the tub. I gave the dog a rub-down with a thick towel, which made up for the soaking, and then I took a hot shower and put on dry clothes. An hour later, my husband came home to find us both bundled in blankets, poor Spike still visibly wet. “What happened here?” What happened was that I took advantage of weather conditions that most people in our region will avoid. I had the streets to myself. The reason this matters in this year of grace, 2020, is that there are still so many mask deniers out there. I live in a hot zone in the state with the highest case count. The statistics don’t phase my neighbors at all. Any time we leave our apartment, we pass more people without masks than people who are wearing them. It’s scary. I’m hoping that many of them are out to enjoy our “endless summer” for as long as it will last, and that they will then grump off inside over the “winter” to binge-watch something. That then it will be safe for me to exercise outside. There’s another reason I hope I can run in the rain this year, and that of course is that I am a COVID survivor. If I can run at all, ever again, it will be a miracle. Running is sort of what got me into this whole mess, but that’s okay. I forgive it. Going by the dates, I was exposed on March 15. I remained asymptomatic until the 31st, sixteen days later. I went for a run on the evening of the 30th, and that was my first real indication that anything might be a little off. Later that night I found out I was exposed. While I’m convinced that the exertion of that run is what tipped the balance for my immune system, I see being able to run again as a major victory over the virus that tried to kill me. In fact, if I go out again, I have every intention of running the exact same route I did that fateful day. I’ve done that before. Several years ago, we used to run in a regional park that was full of gloriously muddy and technical trails. I tripped over a rock, flew through the air, and landed on my face. Covered in bruises, bleeding, I limped home in torn pants. Did my first 5k a couple of days later. When I got home, I made a point of running that route over and over. Each time, I would shape my hand into a laser and “shoot” the rock that had tripped me. I recorded over the bad memory of that fall with dozens of uneventful trips, until finally I erased the anxiety that I had been feeling around that spot. It became my power spot. I would go up there and stand on the bad rock when I had tense phone calls to make or emails to send. I would get it over with, and then I would pause for a moment to appreciate the victory. There has been a lot of negativity directed towards runners during the pandemic, since apparently a lot of people have been out running with no mask on and they don’t distance from people. That is unfair and not how I roll at all. Honestly, when I see people coming I will sometimes go stand in some bushes or walk out in the road rather than pass near them. It ain’t me. I deserve to be able to run outdoors without being afraid of my mask-less neighbors, just like my neighbors deserve to be able to go for a walk without being afraid of me running up and breathing heavily on them. There’s plenty of room for all of us. The difference is, I’ve already been there. I’ve already been flattened by the coronavirus, and I was certain it was going to kill me, and yet somehow I lived when a million others did not. I know it’s real. I still have after-effects months later. Fortunately, the heart palpitations seem to have stopped. I almost never get hand tremors anymore, but I do sometimes when I’m very tired. The symptom that has hung on the longest is the weird thermostat problem. I still wake up shaking with cold probably once a week, even though the night-time lows have been in the high 60s. I will also start shaking with cold outside in temperatures where my husband is right beside me, sweating in shorts. I want to run just so I can feel warm again. It means a lot to feel like I’m starting to get well enough that maybe I could run a quarter-mile, like I tried to do on my very first day. I believe that COVID-19 damaged my heart. That scares me. There were several moments when I was ill and felt like I was moments away from having a heart attack or a stroke. There were a few times when I thought, I should probably call an ambulance, but then it passed. Something interior happens that you have never felt before, and a deep alarm system goes off. Yet running healed me, years ago, and I believe it can do it again. Obviously cells can grow, like we see every time we get a cut and it heals again. Just because there has been damage somewhere doesn’t mean it will never heal. Running helped heal my migraines and my night terrors. Running healed things I never knew it could. I hope I can run in the rain one day soon, and wave my arms over my head, because that will mean I still can. Ever had the kind of day where you just collapse face-first into the couch, pull a blanket over yourself, and cry?

I was having that kind of day. A nine-hour workday including four hours of meetings, a half-hour gap, and then a two-hour meeting for my volunteer commitment. So tired I couldn’t see straight. I couldn’t get warm and my hand tremors were back, one of the lingering after-effects of COVID. I had hit the wall. It’s the same thing in marathon training. You hit your physical limits, and just when you’re already exhausted and in pain, a whole new set of fun symptoms pops out of the closet. Oh, you thought that was a wall? Nope, it turns out it there’s an entire room on the other side! There I lay, trying to will myself to get up and get camera-ready (which did not, in the end, happen. Take me as I am). My hubby came over and started rubbing my back. “It’s only Wednesday!” I wailed. I’m not a crier, as a rule, unless I’m running a distance race. For some reason, running sets off all my emotions. I cry because I love my friends so much, I cry because the weather is so beautiful, I cry because I just set a PR, I cry because I can already imagine the giant meal I’m going to eat at the finish line. None of that bothers me. Crying when I’m ill, though, is something I find humiliating and pathetic. One more thing that makes me feel worse when I really don’t need anything else. I got up after ten minutes - which feels like a long time when you’re bottoming out - and started getting my equipment set up. I was so tired I kept forgetting stuff. “I just made eight trips back and forth for four things!” Then I logged on to my meeting, and everything changed. There were the faces of my friends, colleagues, and companions. This is what gets me through, the same as it does on the race course. Connecting with people I care about somehow taps into a well of energy, even when I’m at my lowest physical ebb. This was a transition meeting, a sort of farewell to the previous year, passing the torch to the new team. Everything is a relay when you think about it. I didn’t feel like I had anything to offer that night. What advice did I have? Uh, try not to die in office? Don’t be me? I felt like I had failed at every single one of the big plans I had at the beginning of the program year. I had campaigned on a platform, and I hadn’t made progress on any of the grand plans I had, nary a one. When I looked back over the past year, I didn’t know how to avoid cataloguing my woes and tribulations: “Let’s see, I started this journey with a root canal and sutures in my mouth, we moved, our dog died, I had an antibiotic-resistant staph infection, had surgery and four stitches in my midsection, was on four separate courses of antibiotics, my husband almost went blind in one eye, and then I almost died of COVID-19. Any questions?” (You’d never guess from looking at me that I recently developed the medical file of an elderly person) But then we went into discussion, and here were the new recruits, so bright and ambitious and excited about the year before them. I welcomed them to start asking questions, and that’s when it turned around for me. Because it wasn’t about me. I never had to rattle off my piteous tale because it was irrelevant to the discussion. Nobody was asking me to explain myself or make excuses for why I didn’t reach all my personal goals. Nobody likely even remembered my platform from last year. What mattered was that somehow or other, we made it. We made it as a team. We kept things together well enough to pass them on to a new group, a new group who wanted only one thing from us: information. Well, actually something more, something that a new group never really realizes they are asking for, which is encouragement. This is one thing I can claim about my leadership skills, that I work hard to make an emotional connection with my team and help reinforce their confidence in their own intuition, their own judgment, their right to lead in their own style. It helps to start out with the assumption that the people you are leading are smarter and more talented than you are, that they’ll surpass you, and that when they inevitably have your job they’ll do it better than you do. If any of that is true, it will mean that you’ve done the most you can do, which is to make others stronger and better than they started. At the beginning of the year, I probably would have pictured myself in full makeup, dazzling everyone with a packet of materials and a carefully polished inspirational speech. Instead I sat at my dining table, wrapped in an old afghan. It was fine. It turns out that what inspires people, one way or another, is all the parts of your personal example that you can’t control. People will form impressions of your behavior that you may never know. (And may prefer not to find out!) What my team shared about working with me was how lucky they felt to be a part of a tight-knit group. In my mind, they built that, and in their minds, I did. Looking back, I have to remind myself of how far I’ve come in four years. I started out so afraid to stand up and speak that my whole body would shake - and now I’m worried about a little hand tremor? I had never even heard of any of the offices I wound up holding or any of the awards I would go on to win. I never dreamed I would serve in a leadership role at all, much less one during a time of such turbulence. I’m still tired, about as tired as I’ve ever been. I still doubt myself and whether I can handle whatever it is I’m currently trying to handle, just as much as I’ve ever doubted myself. Somehow, though, it seems that I keep feeling tired and doubting myself after bigger and bigger accomplishments. This is why it’s important to acknowledge the wall. There is definitely a wall and it definitely feels as materially tangible as any other physical object. Walls, though, can be climbed. They can be toppled. They can serve as infrastructure and you can paint them and grow vines on them. I hit a wall, because I was worn out and feeling sorry for myself. Connecting with other people helped remind me that sometimes we wear ourselves out for good reasons. Just because I’m tired doesn’t mean it’s time to quit, or that I have nothing left. The next time I hit the wall, I wonder where I’ll be and what I’ll be doing? Most of us are probably feeling it, the tangible levels of tension and dread. The restless sleep. The bizarre dreams and outright nightmares.

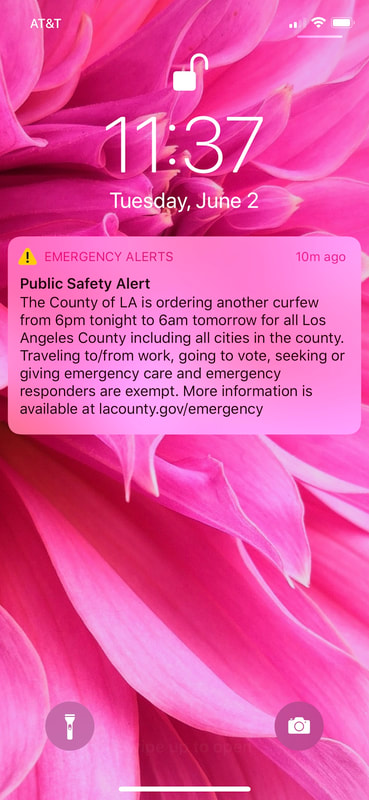

These are the reasons I run. Or used to, before the last time I went out and ran myself into a full-blown case of COVID-19. I’m still recovering, still not totally feeling normal, still having trouble with concentration and focus sometimes. External events are obviously a bigger deal than my private little hassles. Still they are real to me. We all work with what we’ve got. I’ve been trying to rebuild my base level of fitness on a cheap, clunky, creaky elliptical machine next to my bed. I skipped a day, and I paid for it. Wandering around all day with that anxious feeling in the belly, that tax-audit, principal’s office, performance review, collections agency, uhoh Dad’s mad feeling. That Sirens all day Running feet and panting breath in alley below our apartment Protestors marching within a mile of us Helicopters, sirens, helicopters I smell smoke, where is it coming from?? What the heck is going on, will it ever stop What can I personally do Feeling. Sometimes it isn’t clear at all what you can personally do in a situation. Sometimes it takes time to figure out. Sometimes it’s better to stay out of the way. Sometimes you realize you’re in someone else’s movie, and not only are you not the star, you’re not even an extra, in fact you’re blocking the shot. Other times, it’s clear that it’s your time to step up, because you’re the one who is accountable, or you are the only person who can really fix something. Either way, it doesn’t help anyone to have a toxic stew of stress chemicals burning you up from the inside. Burnout is largely physical. We have to pace ourselves, and the more that is on the line, the more important it is... yet paradoxically, the harder it is. The same predictable things happen every time, when we aren’t sleeping, we don’t have enough down time, we aren’t eating right and we have no way of dumping all that cortisol. Our sleep is disturbed even more We lose patience We get snappy, irritable, and mean We feel weepy and we’re not always sure why (except when we are) We can’t think straight We get spun up over even minor decisions Something that is the same in martial arts training and in leadership is a thing called “stress inoculation.” It’s possible to gradually train out the stress response in your body, so that you don’t react the same way even in the most intense conditions. In both roles, you take ownership of yourself as first responder and chief decider. Nobody is coming and it’s your problem to figure out. There is no more time and the moment is now. Some of this comes from having a plan. Some of it comes from having a formally acknowledged title and clearly defined responsibilities. Some of it is just that training in managing the physical stress response. After a while, you feel it. You can feel the difference between when your neurochemicals are messing with you and creating the artificial sense of a real problem, or an actual real problem. For some of us, a crisis is actually less stressful, because it’s obvious what to do. There is a specific issue that might actually go away if the right steps are taken. All this physical anxiety is *for* something. I felt that way when my husband badly hurt his eye and I needed to get him to the hospital. Weirdly, I’ve also felt this way during the stay-at-home order, and again when I got COVID. “Just get through this, nothing else matters right now.” Right now, three days into a riot-induced countywide curfew, I have no idea what to do. So I do what I always do when I don’t have a plan, which is to try to run it off. Five miles a day, miles of nowhere, going yet more nowhere. It feels like a metaphor for life right now. Perpetual motion, tension, stress, with no end in sight and nothing to show for it. Like a hamster on a wheel. For now, at least, the ball of tension is gone. I can chill for an hour or two. Later tonight, sure, I’ll probably wake myself up every two hours. I’ve been having social distancing nightmares - have you? - including walking down the street six feet apart with my ex-husband, and accidentally bumping into the Plandemic lady on the sidewalk. (We both went UGH). This is in addition to the COVID nightmares - fighting a twelve-foot spider with fireplace tools in each hand, millipedes crawling out of my veins, downloading the virus by wi-fi into all our electronics. The sleeping nightmares and the waking nightmares. With all this going on, it’s easy to lose sight of how great it is that I can already do five miles on the elliptical. I survived! I lived through a month of coronavirus and I’m getting my body back! Reclaiming my flesh and staking ownership of myself. In the midst of everything else, I can hit pause for an hour. I can try to get back into my body. I can try to remember that it’s the only vehicle I have to navigate this dumb old world. It isn’t wrong to center yourself, or to sleep, or to do whatever you need to do to restore your focus. There are still 16 or 23 hours a day to worry about everything else. World events will keep happening, whatever they are, for good or ill. One of the few things you can control is your interior ability to cope with things. “I can tell the difference already,” he said. “You’re back up to a seven.”

I’m six weeks into my post-surgery recovery plan, long enough to notice some changes. He’s been out of town just long enough to see that things have changed since he left. These aren’t physical changes in *me* - it’s everything else. The ripple effect. I spent four days rearranging our apartment, including the contents of all our closets and cabinets. The place is gleaming from stem to stern. It’s the sort of thing I like to do as a surprise, or at least the sort of thing I like to do when I’m feeling energetic and upbeat. On the opposite end, one of the first ways I can tell that I’m coming down with something is when I somehow don’t feel like I have enough energy to make the bed. It takes 45 seconds. I’m usually done before I’m even awake enough to realize I’ve done it. If this is disrupted for some reason, it’s a telltale sign that something is off. I rate my mood and energy level on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 on the low end and 10 on the “someone I like is planning a wedding” end. After I took up distance running, I started to realize that it had worked some impressive changes in me. Not in my physique per se, but in my general attitude toward life. “It’s like my baseline mood when I was chronically ill was a 5, or a 4 when I had a migraine. Then when I got better, it was more like a 7. When I’m running it’s like... a 9!” It’s true. When I’m running twenty or thirty miles a week, I feel like I’m getting ready to go to a parade or something. Everything seems simple or easy and I’m brimming over with fun ideas. I used to say I had so much energy, I felt like I could kick down a fence. Sometimes I would be running, and around the 45-minute mark I would just jog along with my arms over my head in victory. Sometimes I would burst into song. Then I blew it. I overtrained and borked my ankle. I had to quit running because I was in so much pain. I would wake up in the middle of the night because it would feel like someone was kicking me in the ankle with a cowboy boot. I had to wear a brace. I had two MRIs and I spent six months in physical therapy. I spent a truly stupid amount of time with my foot in a bucket full of ice cubes. I was mad at myself and mad at my ankle and mad at asphalt and mad that we had to move away from the regional park where I used to train. I used to see other runners pass by and I felt like a dog on a leash, watching other dogs chase a frisbee. Dang it! I changed sports and started getting quite fit doing martial arts. There were physical changes, yes, a different type than the changes that happened when I took up running. It seems that if you dedicate yourself to any one type of training, you can tap into a certain variety of super powers. Running gave me mood powers and endless energy. Martial arts permanently removed my needle phobia and the white-knuckled anxiety I used to feel on airplanes. It helped me eliminate my stage fright. Martial arts gave me an extra dimension of executive presence. I finally learned to really use command tone, and my dog suddenly started paying a lot more attention when I spoke. I learned to make a convincing war face, a crazy expression than can quickly cause people to back up a step with little more than a widening of my eyes. My arms and shoulders bulked up. I found that I could suddenly intimidate big dudes twice my size. For superpowers, these are pretty excellent! I missed the mood effects that I got from running, though. Then I went through a rough patch. I had minor surgery that resulted in an incision right in the middle of my torso. I couldn’t twist, bend, sit up straight, or even move my arms much. After a month of doing hot compresses every two hours, I had to start a routine of changing bandages. This was all very tiresome, but it did provide a massive surge of motivation to start working out again as soon as I legitimately could. I got back on the elliptical. We had to sell ours when we downsized, but there is one in our dinky apartment gym. Nobody is ever down there and I get the whole room to myself. I call it the “news machine.” An hour a night. The first few nights were rough. Not only had I not been working out, I had barely gotten off the couch in two months. I was out of breath and I wanted to quit after twenty minutes. I know how to distract myself, though. I had a long news queue to work through. I focused on how much I wanted to “catch up on reading.” I only let myself do this type of reading during my workout. It felt like a reward. After the first week, it was more like playing a game than exercise. I started getting a taste of the old post-workout glow. If I work out long enough at a high enough level of intensity, I can get an endorphin rush that lasts for two hours or more. It feels awesome, wipes out soreness and fatigue, and helps me sleep better. I didn’t really notice the change as it happened, but over the next several weeks, my baseline mood and energy level started to improve too. A couple of months ago, I was at a real low point. I couldn’t do much of anything, three courses of antibiotics made me sick and headachy, and my incision hurt. I would definitely have agreed that my mood hovered around a five most of the time. Now I’m heading back in the direction where I like to be. I’m starting to feel like the person I think of as the “real me” - upbeat and cheerful. I’m ready to head into Phase Two, where I start running outdoors and enjoying the scenery, hunting for the payoff that keeps all distance runners inspired and motivated. A few months from now, I could be feeling like a nine every day again. Spending time with a group of people that includes a 40-year spread of ages is so revealing. We were talking about where we were in 2010 and where we see ourselves in 2030. One person said, “Ten years ago, I was fourteen?”

Thank goodness, I thought, I’ll never have to go through my teens or twenties again. My skin alone! On the other hand, the most senior member of the group was a bit discomfited by the topic. That happens when you perceive yourself to be closer to the end of your life than the beginning, and at sixty-plus that’s statistically true. (Although such a long way to a 114th birthday, which is possible though still newsworthy). Younger people tend to be very focused on how they look and whether other people think they are good-looking. Probably because they’ve spent their entire lives being photographed. Middle-aged and elderly people tend to be more accepting, or at least philosophical, about their appearance. It can be relaxing. Older people always think you look young and refreshed. My experience with becoming middle-aged has been great. My body has been and looked a lot of ways over the years, enough that I know change is not just possible but inevitable. The trick is that we can conduct body transformation willfully. We can choose to transform our bodies in so many ways. For some reason, our culture seems to revolve around this suspicion that OTHER PEOPLE ARE STARING and that everyone is J U D G I N G. OMG who cares Ride mass transit long enough and you will soon feel like one of the best-looking people of world history. Visit a hospice, or just a nursing home. Just be glad at your relative healthfulness for once. The trick is to turn inward. Direct your attention away from the external and ask yourself what you think of yourself on the inside. How does it feel to be you, to stand up and walk around as you? If it looks culturally beautiful but feels physically terrible, then forget about it. Look at all the paintings of medieval women with high round foreheads, no eyebrows, and big swaying pregnant-looking bellies. That’s what they found attractive. Shave your hairline up to the top of the head, hawt! Then put on a tall pointy hat. Our century of stiletto heels is one day going to look just as ridiculous. Why did all those people limp around bow-legged, grimacing in pain? Why did they carry their shoes and walk barefoot down the sidewalk on festive occasions? What did they wear for warm outer layers? You can’t convince me they just stood in line shivering in the rain. The archaeological record must simply be missing some key garments. This is how I feel about whatever supposed social pressure about how my body is supposed to look: Get back to me after you’ve read my monograph. I read “body acceptance” and “body positivity” now all the time, and what I understand it to mean is “be big enough.” I don’t feel that it literally means “be proud, strong, and muddy.” I truly don’t feel that it means “thin and small is okay too.” I haven’t felt that it includes me or other women like me. That’s okay, though, because I don’t honestly care that much! I don’t care because I’ve felt my own body transformations over the years. I have lived a body that is different from one year to the next, sometimes by accident, sometimes through intense bouts of purpose. There is no way I’m going to trade my strong body for a weaker version just because it’s trendy. Twenty years ago, I wore a clothing size that was six to eight sizes bigger than I wear today. Weirdly, my body weight is only about ten pounds lower. That’s because I dropped about forty pounds of body fat and built about thirty pounds of muscle. It sounds hard to believe. I should probably dig up some old photos and spreadsheets for documentation. Again, though, it’s my body to live in and inhabit, and my body is not an object for society to critique. It’s my home. In my early twenties, I was ill. I went to a lot of doctors who did not have a lot of answers. I felt tired and ill all the time. I fainted at the grocery store a couple times. I saw black spots when I walked up a flight of stairs. For a young woman, I felt like an old woman, one who clutched railings. Now I’m in my forties, old enough to be the mother of my younger self. I feel like I could pick up Younger Me and carry her up the stairs. Maybe not a fireman’s carry but certainly a piggyback. Younger Me would have been angry and hurt to feel so judged by Today Me. Get up, get up, I want to tell her. Don’t quit! There is still time for you! I look how I look, she thought, just like I do today. At the time, though, she believed in a fixed body. That how we look is a million percent genetic. That the head of anyone who thinks differently should simply explode, because nothing is stronger than my internal rebellion or determination of my identity, of what counts as me. It turns out that that same resistant feeling was exactly what I needed to propel me up a lot of hills, along thousands of miles, through hundreds of burpees and all the rest. My rage at anyone who dared tell me about my body or criticize my personal autonomy, that was the fire that consumed Young Me. Stubborn, I found myself a warrior of sorts. When I was young, I felt just as judged as any other young woman. As an adult, I find it hilarious to walk around covered in mud, or carrying my kali stick. Men, even very very large men, get very squirmy and nervous when they find out I do martial arts. “Just don’t attack me and you’ll be fine,” I say, which usually makes it worse. Posture is what makes the change. A vertical posture says a lot. A comfortable stance says more. I reside in a strong body and I can use it to do some pretty surprising things. Ten years ago, none of that was true, because I hadn’t yet seized ownership of my identity as a midlife athlete. Today, I feel that I will be stronger at sixty than I was at thirty. I know it will be true because I know how to make decisions and I know how it is done. Not everyone realizes this, but it’s not okay to change your fitness routine. It’s not okay - it’s MANDATORY. First of all, doing the same routine over and over can eventually lead to stress injuries. Second, it’s boring. Third, the body adjusts and the law of diminishing returns sets in. Perhaps most importantly, any single routine may neglect entire areas of the body. This is why it’s so vital - and fun - to occasionally pause and pivot.

I first started switching up my workout because my college gym had strict 30-minute cardio sessions. If you tried to stay on the machine longer, a bouncer would come over with a clipboard and evict you. I used the cardio equipment while I read my homework, and a half hour wasn’t enough. I learned that I could get a better/longer workout if I signed up for adjacent time slots and simply moved from one machine to another. I also learned that more than five minutes on the stair climber made me want to barf. Sometimes all the cardio machines would be booked. That’s when I started learning to use the weight machines. I was getting over a bad breakup, so my girlfriends would spot me and encourage me and keep me company. That boy was no gym rat and it was one place on campus where I could sulk in peace. I started to see the gym as a place of refuge, a solace, and a mood adjuster. Over the next fifteen years, I learned that Gym Me had high energy and a good mood, while Default Me was mopey and got sick a lot. I also had to change what I was doing many times due to relocation, job change, injury, or forgetting who Gym Me was. For a while. Being fit has a tendency to reveal mysterious superpowers that weren’t even what you were training for. I’ve astonished myself with the suddenly revealed ability to climb a rope, do a headstand, or whip out a new hula hoop trick after watching someone else do it for a few seconds. The fun stuff! The fun stuff, like toppling a 250-pound huge dude with a jiu jitsu throw. I’m doing a pause and pivot right now. It’s been really emotional and difficult, because I’m stubborn as all-get-out, but it has to be done. I recognize this. It’s my own idea and my own plan, and still I’m struggling with my traitorous emotions. My feelings, always getting in my way and trying to ruin my strategic vision. I’ve been enrolled in a martial arts school for nearly a year and a half. I convinced my husband to join, and we’ve been going to kickboxing classes together, a lot of the time at least. There have been problems, though. On his end, he’s lost nearly twenty pounds. His neck mobility has vastly improved and his chronic back pain is almost completely gone. He revels in fighting and he’s been getting the blue belts to teach him higher level secrets. He’s in the best shape of the fourteen years I’ve known him. He’s as happy and excited as a little kid with his first skateboard. On my end, I’ve been going through several months of health struggles. I got a bad cold in the beginning of August, and that somehow turned into being sick 40% of the time between August and January. I missed (and paid for) weeks of classes, which unfortunately cost 25% more because I had just leveled up to the advanced classes. I went to the doctor to find out why I kept getting sick, fearing the worst, and she said she had known a fellow doctor who had the same problem. She wasn’t getting enough sleep during her residency, her stress level was high, and she could never quite recover fully before she was exposed to another cold. This doctor told me I would probably keep getting sick until the end of this year’s cold and flu season. Wow. Neat. I mean, at least my blood work is good. I did some research on my own end. It turns out that intense exercise can lead to being more vulnerable to colds and flu. Yeah. It makes sense. I would keep pushing myself a little too hard and trying to get back into classes a little too soon. I’d start going out and trying to work out at my normal intensity every time I reached 80% recovery. It was like trying to shut a door and having a mosquito fly in. Again and again and again. After literally the twelfth time I got sick in eight months, I finally realized I had had enough. I need to give myself a break before I wind up on an inhaler. I paused my gym membership and told everyone I’d be back in six months or so. This has nothing to do with grit or perseverance or fortitude. Those are the qualities that got me into this mess. This also has nothing to do with abdicating on my body and burrowing into a recliner. I know I can’t do that because sedentary behavior impacts my thyroid, and I feel far, far worse when I sit around all the time. This is a sabbatical, a pause and a pivot. The first thing I’m going to do is to get over this most recent cold. I’ve been organizing my digital files, catching up on email, reading, and sleeping as much as I can between my neighbors’ centaur races or whatever they’re doing up there. My pivot is to focus more on cardio over the summer. My husband and I talked it out, and remembered that when I was training for my marathon, I felt great all the time and I never got sick. I didn’t get sick that entire year! The only reason I quit was that I overtrained my ankle and wound up in physical therapy for six months. I know more about stretching and cross-training now. I also know the warning signs. There’s no way I’ll do that to myself again. The other thing is that I gained fifteen pounds in my shift from endurance running to boxing. Granted, some of it is muscle, but it doesn’t seem to be doing me many favors. My weight regain is perfectly correlated with the return of my night terrors, migraines, and vulnerability to seemingly every passing airborne virus. It’s gotta go. The great thing about testing weight gain or loss as a variable is that it’s temporary. If you don’t like the results, you can always go back in the other direction. If I lose “too much weight” I can just eat more and put it back on over the weekend. *shrug* The most important factor in a pause and pivot is the feeling of returning to center, of fully inhabiting one’s physical vessel. I am my body and my body is me. High energy is my birthright. I’ll do whatever I need to do to take care of myself and give myself the utmost strength and mobility. On social media, a lot of people spend a lot of time saying a lot of things that make them indistinguishable from bots. There could be entire predictive text buttons with these bumper-sticker sentiments. You could even write a script that posted them for you while you went off to make a sandwich. Of all these repetitive, commonplace reactions, Quit Posting Your Workouts is one of the most common. After consideration, I tend to agree. I used to post my workouts to Facebook, and I quit... Facebook. If you’ve been frustrated by this particular issue, pro or con, maybe my outlook will be interesting.

Here’s the thing. Everyone does something that is interesting to some friends, irrelevant to others, and annoying to yet others. If we remove all of these topics, what could there possibly be left to talk about? My workout is a significant chunk of my day and my life. It’s an enormous part of who I am. It’s how I beat illness, it’s a constant research topic, it’s an area where I explore and learn new things, it’s where I see and hear much of what I find interesting. It’s also where I now make most of my friends. Asking me never to share about this part of my life is precisely like asking someone else never to talk about their kids, their job, their home remodel, or any of their hobbies. Wouldn’t it be nicer to just unfollow, scroll past, or otherwise ignore posts that don’t interest you? Maybe, like me, you’ve posted about workouts in the hopes of connecting with your other friends who also work out. Maybe, like me, some of your friends cross-train, and thus can’t capture everything we’re doing through an app like RunKeeper. Maybe, like me, you have a years-long running conversation with a small group of friends who are constantly exploring different types of workout. Maybe those conversations are one of your main reasons for ever logging on to social media at all. If there’s ever a more suitable social media platform for us, one without all the non-workout BS, we’ll all stampede toward it and never look back. Or maybe you’re one of the forty percent of Americans who never do any kind of exercise whatsoever, not even walking for fifteen minutes. Maybe all this talk just irritates you to no end. I dunno. What I found was that sharing my workouts tended to generate friction for a variety of reasons. It brought up disagreements and mean comments from people who I had previously liked, people I considered my actual friends before social media came along and ruined it. I exercise because when I don’t, I suffer physically, and I don’t really feel like I have an option. For whatever reason, other people interpret this as body shaming, as buying into the beauty myth, as some kind of psychological problem, as proselytizing, or as just being a terminal bore. I started to realize that it really wasn’t worth my time to engage in discussions where words were put in my mouth. Why go there if my character was going to be brought into question or my motives were misinterpreted? This is part of the picture when people say that when your energy changes, your friends change. It’s not always that you become some sort of social climber and abandon your previous loyalties. It’s more that your new thoughts, behaviors, and conversation topics annoy your old friends, who can no longer stand you and don’t want to socialize with you unless you go back to your old ways. If you want to know, my weekday workout typically looks like this: Ride bike along the beach to martial arts gym while listening to an audio book. See my friends. Crush it for an hour, learning new things, surprising myself with what my body can do that it couldn’t do a month ago, bonding with people from all walks of life. Gossip in the changing room. Ride home along the beach again. Walk the dog. Do an hour on the elliptical, reading articles about space, biomimicry, and robotics for my tech newsletter. Stretch for half an hour. Shower. Sometimes this all starts in the morning, sometimes in the evening. Some days I work out for nearly three hours. That might sound extreme, but I do longer workouts a few times a year. Distance days for marathon training were two to three hours once a week. Martial arts belt promotions go for four hours. I’ve gone on four-hour bike rides many times. When I go backpacking, we typically hike for six hours or more. On vacation I walk eight to ten miles a day, basically from morning til night except for meal breaks. For someone who enjoys endurance sports, “time on feet” is a valuable training metric. I’ve had several jobs where I stood for forty hours a week. I think back to our pioneer ancestors, who walked thirty miles a day on the Oregon Trail, and I seriously question a modern society that thinks sitting or lying down for 20-22 hours a day is somehow normal. The more I find that I can do routinely, the more I wonder how much is out there for me. In my life, what I do for exercise is equivalent to what I do for reading. I see both as exploration and adventure, as a legitimate intellectual inquiry. Both are endlessly fascinating and irresistibly attractive to me. The alternative to both I see as “sitting in front of a television for five hours a day,” which is something I did throughout childhood and now find impossibly boring. I took everyone’s advice and quit posting my workouts. I write about them, sure, and if someone wants to touch base with me and find out what I’m doing these days, Wednesdays are the day for that. Otherwise, some of my most interesting conversations are happening in person, live, in my gym. For those of you who are likewise confounded by constant social pushback, don’t let it get to you. Just move the conversation to a place where it’s appreciated and leave everyone else to go about their business. This is bad. THIS is the kind of thing that makes me feel old. Here I am trying to do the splits, and I can barely get my legs in a V. How am I ever supposed to turn a cartwheel at this rate? I’m looking at this book with a bunch of granny ladies grinning while they stretch, elbows on the floor, and feeling like I have barely half their agility. Darn it! I’m reading Even the Stiffest People Can Do the Splits, and right now it feels like I’m going to need a lot more than four weeks.

I’m a pretty bendy person. Other people may have trouble touching their toes, but I can fold over and put my palms on the floor. I can sit down, stretch my legs in front of me, and grab the arches of my feet. No problem! I can reach one hand over my shoulder and the other up my back and clasp my fingers. I can do a headstand and I can spin two hula hoops at once. I like to think of myself as more agile than most. So why is it so hard to do the splits? This is a non-trivial problem, dumb as it may sound. My tight hips are likely behind some chronic problems. My current working hypothesis is that spending a month (or six) stretching and improving my mobility in this area will help to resolve these other issues. If I’m wrong, well, I probably won’t be any worse off, and I’ll be able to do the splits, which is rad. What are these tight hip problems? For one, my glutes on one side or the other will sometimes seize up so much that I start limping. This is bad for someone in her forties, and I imagine it would only get worse with each decade that goes by. I do NOT want to find out what it’s like to have a permanent limp. Next, I sometimes have some pretty fierce plantar fasciitis pain in my heel or the arch of my foot. This is weirdly worse when I’ve been sedentary; it didn’t bother me at all during my months of marathon training, and it’s more likely to flare up after my second rest day in a row. It was worst the first year after I quit my day job, when I basically slept all day. It disappeared after I became obsessed with the hula hoop. Right now it seems to have been reactivated by my martial arts training. A couple of times it’s woken me up in the middle of the night. I was sidelined from running by persistent ankle pain. Two MRIs and six months of physical therapy didn’t really resolve it. Talking to a personal trainer at the gym revealed some insights, and two months of weekly shiatsu massage focusing on my shins finally eliminated the ankle pain. The trainer said it originated in hip instability, and that endurance running tends to lead to weak hip flexors, glutes, quads, and core. True, that feels true. Martial arts training is definitely, visibly building these areas. Hundreds of snap kicks and jump squats will do a lot for your hip flexors, if nothing else! I’m finding, though, that I have a lot of trouble with roundhouse kicks, and that I feel a pinch when I do it at the correct angle that my classmates don’t seem to be experiencing. Even if I get nothing else from working on the splits, it seems obvious that it will help improve my roundhouse kick. I gotta tell you, though, it hurts. I was able to train into the headstand in only two weeks, and that just felt like fun. (Except for the one night when I toppled over, smacked my caboose on the floor, and woke up in the morning with a limp that lasted about three hours). Doing the recommended stretches to work into the splits? Is NOT fun. It’s so sore. Where do tight hips come from? Sitting, I imagine. I spent almost all my time sitting from my teenage years through my early thirties, partly due to my secretarial job. Or driving. I think driving causes more tightness on one side because we’re pressing on the gas pedal and leaning to one side to shift gears. Also we’re wearing seatbelts that cross over one side, and we tend to wear our bags on the same shoulder all the time, weighing one side down more than the other. These are extremely common issues, and they suggest that a lot of people are having some of the same issues that I am. I can also claim years of running and cycling as contributors. As much as I love racking up the miles in my endurance sports, they cause repetitive movement along only one axis. Forward forward forward. I want to do a fifty-mile ultramarathon for my fiftieth birthday, and it makes sense to work on my hip tightness before setting out on that type of training. I’ll be super annoyed if I have to cancel my plans due to a recurrence of the same ankle problem I had before. This is what I think about while I’m sitting on the floor, trying to coax my unwilling muscles to loosen up. Legs, I need more from you! This is where I remind myself that twenty years ago, I was diagnosed with fibromyalgia. I had trouble just getting through the day, and sometimes I couldn’t get out of bed in the morning without help. I’ve come a long way! I can’t help but wonder if doing this type of stretching back then would have helped. I sure wish I had, because with twenty years of daily practice anybody could probably do pretty much anything. Isn’t that what physical therapy is, after all? Daily practice, daily practice. My fitness role models are all over sixty years of age, and many are over eighty. This is because I’m very concerned that Old Me should be able to get around, climb stairs, sit on the floor and get up again, and carry things. She deserves to keep her independence. I remind myself that if I live to my eighties, I’ll have fifteen thousand days to get down and stretch. If that isn’t enough time for my muscles and tendons to adapt, maybe by then I can just download my consciousness into a robotic avatar and sign off on the whole project. |

AuthorI've been working with chronic disorganization, squalor, and hoarding for over 20 years. I'm also a marathon runner who was diagnosed with fibromyalgia and thyroid disease 17 years ago. This website uses marketing and tracking technologies. Opting out of this will opt you out of all cookies, except for those needed to run the website. Note that some products may not work as well without tracking cookies. Opt Out of CookiesArchives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed